The Fog Economy: What If This Is Stagflation?

When stagflation last arrived, we saw gas lines and garbage piles. Today brings empty shelves and ships that never dock. As indicators contradict and familiar policies fail, history isn't repeating—it's mutating. We're entering a new economic fog, not by accident but by deliberate policy choice.

1. The Fog.

This moment does not feel like anything most Americans have lived through. We are used to extremes we can name – the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID shutdowns, bull markets, bailouts, layoffs. Clear stories, sharp edges.

Now the edges are gone. The economy doesn’t crash or soar; it stalls, slips, lingers. Prices drift higher without rhythm. Hiring cools in one city, heats in the next. The numbers we do have flicker like broken signals. We might be fine. We might already be in a deep recession. We could even be growing and not feel it. Nothing behaves the way the models say it should, because those models were built for a world where the ships still came.

At the ports the change is visible in what is missing. Berths at Los Angeles and Long Beach are open, cranes stand still, and the harbor pilots wait for ships that are no longer on the schedule. Executives at the port warn that incoming cargo will fall more than thirty‑five percent after President Trump’s new tariffs, with a quarter of vessel calls already canceled.

Inside the stores nothing looks empty yet, but choice is thinning. You want a blue shirt, you find eleven purple ones and one blue that is not your size – and that lone shirt costs more every week.

Everyone is waiting for something solid. And in that waiting a word has returned, quiet and unwelcome:

Stagflation.

It is more than an economic condition. It is a memory of the last time nothing worked, the 1970s, when prices outran wages for a decade and confidence eroded grain by grain.

For the first time in a generation we are drifting toward that edge again, not because of an earthquake in markets, but because of policy – tariffs that choke trade, prices that rise on command, a pause that spreads from the docks to the dinner table.

Even the Federal Reserve admits it cannot see the road. The numbers clash, the usual tools misfire, and the sense that no one is steering is what makes this fog so heavy.

To understand why this feels so uneasy, we have to go back to the last time inflation, stagnation, and uncertainty collided – and every familiar lever failed.

2. The Last Time It Happened.

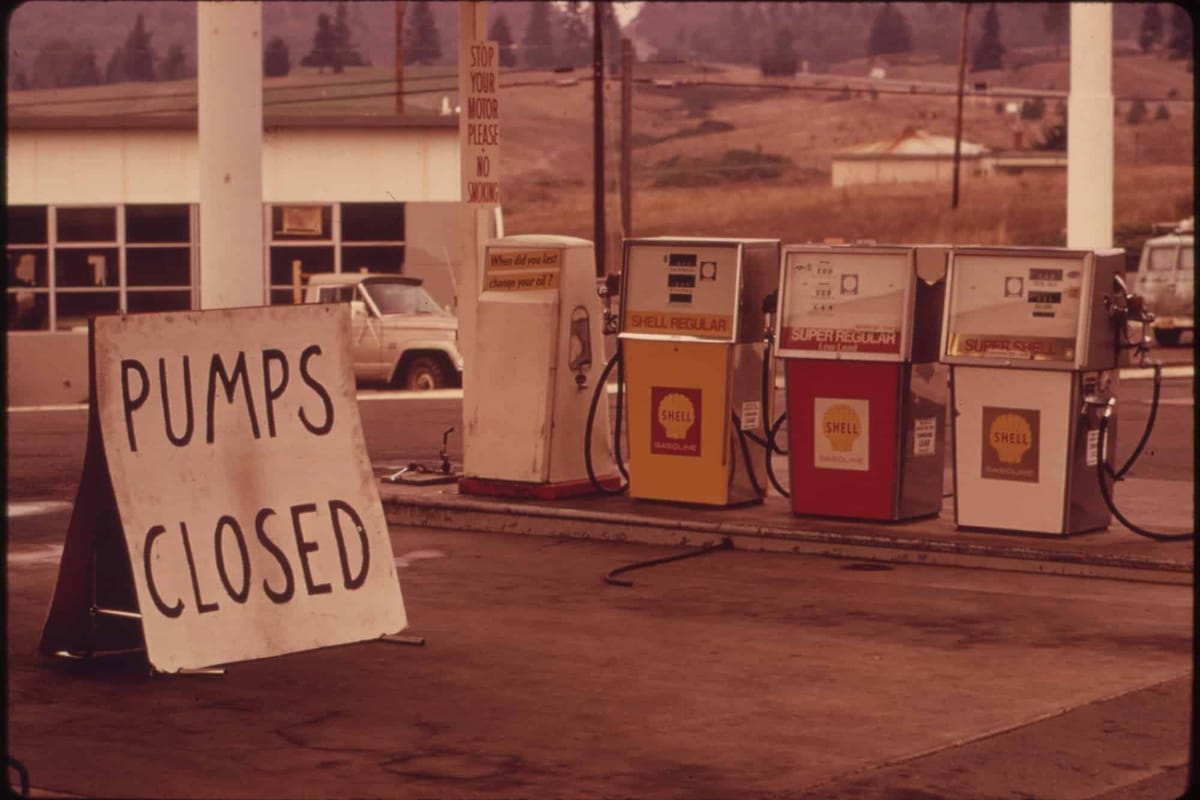

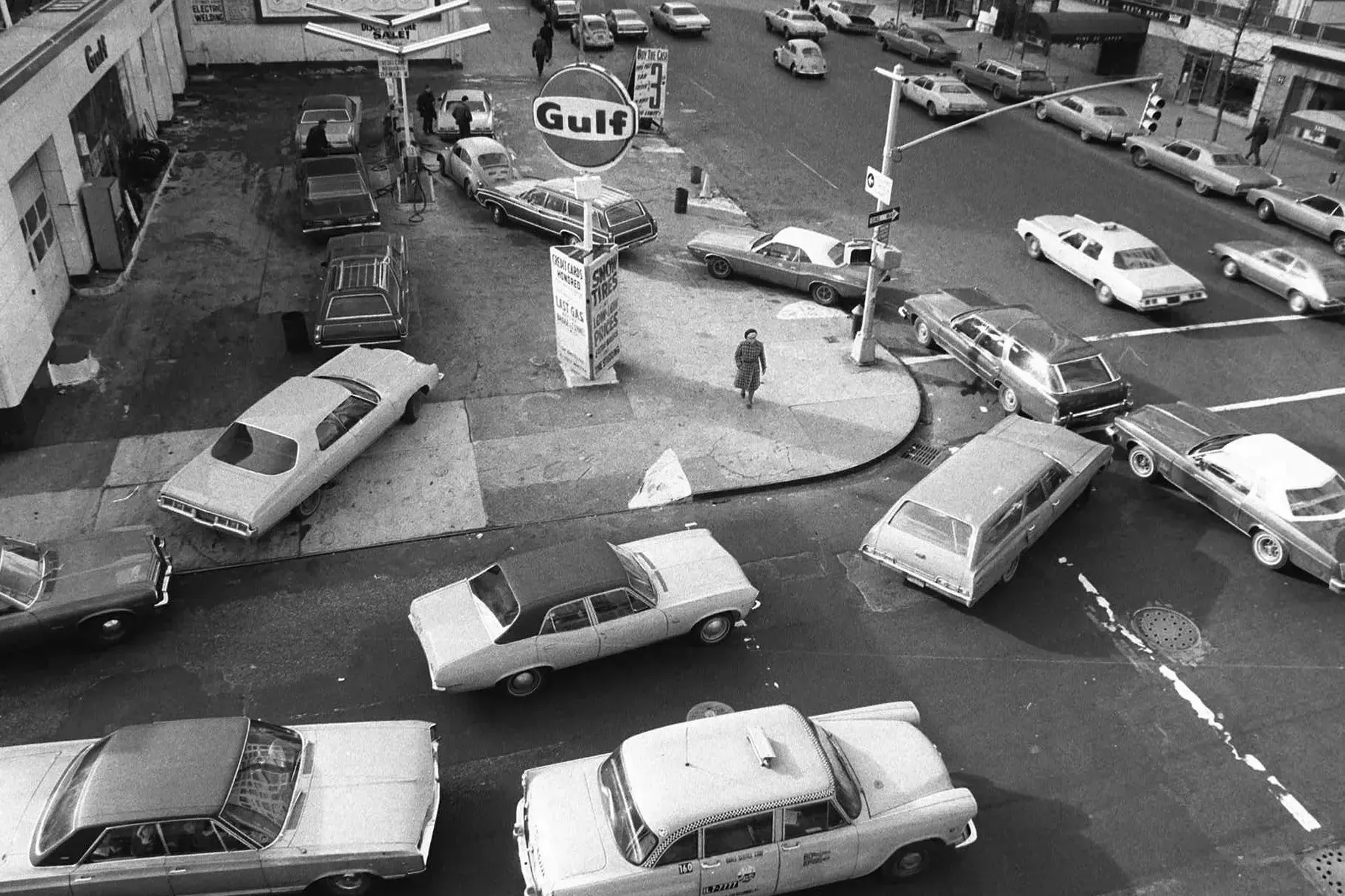

he 1970s were the last time the global economy confronted stagflation. We tend to remember those years in fragments: oil lines in California, garbage piling up in Britain, the collapse of the Alberta economy. But these weren’t just moments. They lasted for years. And at the time, no one knew how – or even if – we would get out. The fog of economic uncertainty wasn’t new. It was global. It was generational. And we only ever half-understood how we made it through.

During the gas crisis, my mother took turns carpooling with other teachers at her Oakland school, commuting down Telegraph Avenue. She drove a white Chevy Valiant. They each drove one day, saving fuel, watching the gas gauge. Whether you could fill your tank depended on the last digit of your license plate — odd-numbered plates one day, even the next.

But by 1979, inflation had eaten into her teacher's salary so deeply that she began skipping lunch. Not by choice — by necessity. From the quiet, invisible calculus that told her: food or rent. Over the course of a year, she lost ten pounds. That, too, was the fog.

Americans waited in line for fuel. Waited for wages to catch up with prices. No one knew why inflation kept rising as the economy slowed. Nixon froze wages and prices in 1971, the first peacetime controls of their kind. In 1974 President Ford handed out "WIN" lapel pins — Whip Inflation Now — as if morale might substitute for monetary policy. The Federal Reserve lurched between tightening and easing. Congress passed stimulus packages. The government flirted with rationing. None of it worked. Each failed experiment deepened the uncertainty. Policymakers didn't just fear inflation — they feared irrelevance. And through it all, inflation kept climbing.

And this wasn’t just a United States story. The fog crossed every border.

In Canada, the 1973 oil crisis seemed at first like an escape route. While much of the world stumbled, Canada briefly believed it had found a way through. Alberta’s oil economy exploded, selling crude to a desperate United States. The province surged with cash, even as other parts of the country fell behind. The wealth gap deepened regional divides. In British Columbia and Alberta, inflation and unemployment swung wildly, fueling backlash and resentment. Populist parties surged. Western separatism found new life. The mood turned brittle.

And then world oil prices collapsed.

By 1981, inflation in Canada peaked at 12.5 % and mortgage rates topped 20 %. Ottawa tried wage‑and‑price controls, but the disorientation ran deeper than policy.

The Bank of Canada tried to chart a course through the chaos. But it too was lost in the fog. Internal documents reveal how little the bank understood what it was fighting. Models broke down. Policymakers second‑guessed every move. Interest rates spiked. Growth stalled. The pain was real, but the path forward was not.

Canada didn’t just suffer a recession. It lost most of the 1970s and 1980s. Even Alberta, once flush with boomtown money, slipped into a deep, grinding downturn. Unemployment in the province topped 13 percent in 1983. Friends of mine remember their parents losing their jobs – and then their homes. Entire communities unravelled beneath the weight of vanished certainty. The fog of stagflation lingered long after the numbers began to recover. For much of the country, the decade didn’t just hurt – it changed what people believed was possible.

In the United Kingdom, the fog was thickest in daily life. Inflation hit 24.2% in 1975 and stayed above 10% for most of the decade. The pound was devalued again and again. Strikes became a regular feature of the economy. Garbage piled up in the streets. Hospitals went dark. Electricity was rationed to three days a week. Newspapers stopped printing. TV stations signed off by 10 p.m. Even the morgue workers went on strike. Bodies were left uncollected. Wages couldn’t keep up with prices, and trust collapsed alongside paychecks. And the UK was at war with itself: the conflict in Northern Ireland escalated into deadly violence, killing thousands of Britons and fracturing the country’s sense of stability.

Stagflation in Britain didn’t just mean prices rising and growth slowing. It meant a kind of institutional exhaustion. A feeling that the future was slipping out of reach. The fog settled not just over the economy, but over the idea of Britain itself.

Other countries met the fog, too. But none lived in it as long – or adapted to it as deeply – as Japan.

In the US, the turning point came with Paul Volcker’s “shock therapy” at the Federal Reserve. Beginning in 1979, Volcker raised the federal funds rate from around 10% to a peak of 20% in June 1981. The result was the worst recession since the Great Depression. Unemployment rose to 10.8% by the end of 1982. New home construction dropped by over 50%. Farm bankruptcies surged, especially in the Midwest. Protests broke out outside Fed buildings. Farmers mailed Volcker coffins. Homebuilders sent him two-by-fours wrapped in black crepe. In steel towns the Fed became a curse word. But inflation, which had been stuck above 10% for years, finally fell to 3.2% by 1983. The cure was nearly as painful as the disease — and deeply controversial at the time.

In the UK, Margaret Thatcher pursued her own brand of economic shock. Her government slashed public spending, raised interest rates to 17% in 1979, and prioritized fighting inflation even as it sparked recession. Industrial output fell by 15% in just two years. Entire communities in Northern England and Wales – built around coal, steel, and shipping – were hollowed out. Unemployment surpassed 3 million in 1982. But inflation, which had peaked at 18% in 1980, fell below 5% by 1983. The economic pain was lasting, but so was the disinflation.

None of these exits were clean. Each came with deep social costs. What cleared the fog wasn’t just policy – it was time, credibility, and a slow reweaving of institutional trust. And even then, it wasn’t guaranteed to last.

Japan’s fog came later, but lasted longer. After the asset bubble burst in 1990, growth slowed to just 1.14% annually through 2003. They called it the Lost Decade. And then the Lost Decades. Banks refused to recognize losses. Companies hoarded cash. By 2001, Japan’s economy was no larger than in 1995. An entire generation came of age in stagnation. They were called the Lost Generation []. Even with interest rates at zero, deflation made risk unthinkable. And thirty years later, Japan still hasn’t escaped. It remains a warning: the fog, once settled, can become the new normal.

That’s the difference now. This time, the fog isn’t creeping. It isn’t misunderstood. It isn’t the accidental byproduct of drift.

It’s being chosen.

3. Off The Map.

Today is May 7, 2025. Amazon stopped selling my favorite toilet paper brand. The Chinese seller I ordered a power adapter from canceled the order without explanation. These aren't headlines. They're not even footnotes. But they are also signs.

We are waiting for something to break — a crash, a market collapse, a definitive moment that tells us where we are. Since the end of the 1970s, that's how recessions have worked. They arrive with a cause and end with a rebound. The dot-com boom led to the dot-com crash. COVID caused a deep recession, then an historic recovery. The logic was linear. Inputs and outputs. Disruption and bounceback.

But stagflation doesn't follow that arc. It doesn't even have a clear beginning. The last time it appeared, in the 1970s, no one could agree on what caused it. The US economy had been booming through the 1960s. Unemployment hit 3.4% in 1968, the lowest level recorded since World War II. Canada was growing. So was the UK. Then the fog arrived.

In Japan, it was the same. An unprecedented economic expansion — rising exports, rising wages, an ascendant middle class — gave way to a long, low unwinding. When the bubble burst in 1991, it left behind not just losses but disorientation. Growth slowed to a crawl. And for thirty years, it never really came back.

Now we are entering something new. Or something old in disguise. The tariffs Trump imposed in April are real and massive. They are a deliberate policy intervention, not an accident. But no one — no central bank, no business, no economist — knows what a supply shock of this size will do. We are off the map.

The economy might be fine. Or it might be in freefall. We simply don't know. Retailers had stocked up ahead of the tariffs, which is why store shelves haven't emptied. Yet. But when the frontloaded goods run out, we may start to feel what's really happening. Or maybe we won't.

That's the fog. Not just the facts we lack, but the meaning that won't come into focus. It's terrifying — not only for households trying to plan a future, but for the institutions meant to steer us through.

This is what makes the current moment so dangerous. Not just the tariffs. Not just the trade collapse. But the uncertainty that follows. The wait for a signal that may never arrive. And the growing fear that we've already passed the moment where something should have happened — and nothing did.

That's why people aren't moving. That's why businesses are holding back. That's how stagnation begins.

We know how to handle recessions. We stimulate demand. We cut rates. We inject liquidity into the system. And in most cases, that works. It restarts hiring, revives consumption, and steadies the market.

But this time, there may be nothing to buy. Stimulating demand in the face of a massive supply shock will only push prices higher. That's not a hypothetical — it's what the Federal Reserve warned us about today. Today, Chair Jerome Powell described a period of "heightened uncertainty," driven by "tariff-related sentiment shocks" and a "decline in forward-looking confidence metrics." In other words, we are not just watching demand slow — we are watching the supply vanish, and with it, the meaning of our metrics. Inflation won't fall if goods stop arriving. Interest rates won't help if inventory never clears a port.

That's what made the 1970s so hard to escape. Even top economists couldn't agree on what had gone wrong. Some pointed to oil shocks. Others blamed fiscal excess, loose monetary policy, or global structural shifts. But the real damage came from indecision. Policymakers hesitated too long, trapped between painful cures and worsening symptoms.

And when they did act — through austerity, wage controls, or rapid tightening — their moves often backfired. Countries that imposed austerity during inflationary periods saw deeper recessions, lower output, and long-lasting political instability.

That's why this moment is so dangerous. The fog doesn't just disorient households. It paralyzes institutions. It makes policymakers afraid to move — and punished when they do.

That's not just a recession.

That's stagflation.